'Non-Nurse' Midwifery Her-Story in the US

- Augustine Colebrook

- Sep 6, 2021

- 19 min read

As a modern midwife, an anthropology major in college and with a masters degree in maternal child health systems, I find it particularly interesting to examine the legacy of my profession from a sociological perspective. Sociology, most simply is the study of the social behavior or society, including its origins, development, organization, networks, and institutions. It is social science that uses various methods of empirical investigation and critical analysis to develop a body of knowledge about social order, disorder, and change.

Note to the reader: The following encompasses the paths to midwifery recognized by U.S. national midwifery organizations that adhere to formal accreditation and certification processes. This article and this literature review do not intend to devalue or delegitimize any of the indigenous and various heritages of midwifery traditions in America’s past, present, or future.

Midwifery as a body of knowledge and a physical practice has been in existence since the beginning of time. And traditionally, midwives had a much broader scope of practice than we know today. They were not just birth attendants, but also family/community healers for almost all aliments - this continued from antiquity to the end of the 19th century. The midwives that practiced during this time, had a much broader scope than is currently practiced. Midwives practicing in the south were affectionately called, 'Granny Midwives' and indeed, midwifery, much like priesthood was not a profession you retired from.

Granny Midwives 1800s - 1920s

Yet midwifery in the U.S. has a complicated history, convoluted educational paths, and varied legal status state to state. In short, the consumer is often confused about training, scope, and legal status nationwide. Traditionally, midwives had a much broader scope of practice than we know today (Davis-Floyd, 2006). They were not just birth attendants, but also family and community healers for almost all ailments until the end of the 19th century. The description below, from an early Euro-American context, summarizes midwifery practice well.

“Home was still the place of birth in the early 19th century, and the average American woman gave birth to six children, not including children lost to miscarriages and stillbirths. Only women midwives attended women during childbirth. (In later years there were male midwives.) These women were skilled in assisting the woman by providing comfort measures, nourishment and nurturing, and by patiently waiting for nature to take its course without undue interference with the normal process of labor and birth. ... Midwives were local women, usually with children of their own, who had learned midwifery as apprentices, as did many 19th century physicians. Observing and helping with deliveries honed their skills and exposed them to the variety of problems they would face when working on their own. For their work, midwives might receive modest compensation, however, they might be paid with a chicken or household goods” (History of American Women, 2018, para.07).

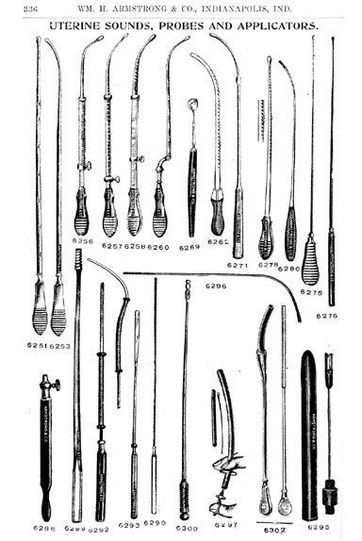

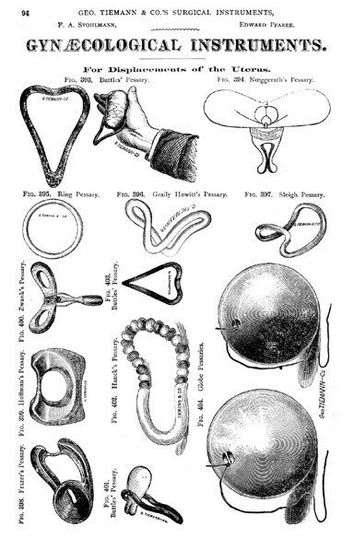

Extensive knowledge of herbal identification, harvest, preparation, dosage and administration was a chief component of the midwives' skill set. In the United States this expertise was a backbone of all communities until approximately the 1930s (Wertz & Wertz, 1989). Although 'barber-surgeons' in New England were the first to displace midwives as the primary healers and birth attendants as in the big cities of New York, Boston, and Philadelphia, laying-in hospitals started offering pain relief in the form of ether or chloroform in the first decade of the 20th century (Wertz & Wertz, 1989). The appeal for women to be out of pain during labor, as well as the public relations campaign of ‘birth cleanliness’ in an institution was enough of an incentive for some to leave their homes and to birth in these hospitals (Ehrenreich & English, 2010; Scott, 2013; Wertz & Wertz, 1989).

"As one resident of Taney County, Missouri, remembered:

The nearest doctor was 20 miles away and there was no way to travel only horseback and no money to pay with if he did come. . . . Mother watched over us carefully. There wasn’t money to buy medicine. In the spring she would make sassafras and sage tea to condition our blood. In the summer and autumn we would eat . . . anything we found growing wild, without washing it. Naturally, we would get “wormy.” knew the symptoms. Some morning before breakfast she would stir up a mixture of wormfuge in a skillet of molasses. . . . Before night we were rid of our worms. If one of us needed a tonic Mother went to the woods, peeled some bark from a wild cherry tree, dug some sarsaparilla, some blackroot, and other herbs (I have forgotten), boiled a brew out of it and gave it in regulated doses. . . . She made tea of pennyroyal, mullein, and tansy for our stomach cramps; slippery elm she made poultices of and applied to boils. . . . I have often heard Mother wish she would have studied medicine and have been a doctor. She would have made a good one." <1>

Ghost Midwives 1930s - 1950s

"To gain more clinical practice, established lying-in hospitals or wards in major hospitals. Sepsis was unknown, so, with unclean hands and tools, physicians examined women and tended to the birth of their babies, leading to epidemics of puerperal fever, which caused thousands of maternal deaths. Fortunately, many individuals contributed to understanding the cause of puerperal fever, including Ignaz Semmelweis, a renowned Hungarian physician; Oliver Wendell Holmes, an American physician; Louis Pasteur, a French scientist; and Joseph Lister, an English surgeon. By the end of the 19th century, germ theory was finally accepted, and the advent of anesthesia made surgery safer and free of pain. Anesthesia administered for pain in childbirth became desirable for many women who chose physicians as their birth attendants.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, American obstetricians sought to overtake the entire field of childbirth and declare major war against the traditional midwives in the United States. Midwives wanted an education, but obstetricians fought hard against this idea.

"Schools for midwifery education were established in European cities, and European health care created a dual system by which midwives continued to attend normal births while physicians handled complications. This did not happen in the United States. American physicians fought hard against midwifery education, in spite of midwives wanting an education, which public-health reformers supported. In the early 20th century, many midwives still practiced in rural, remote areas of the country and with inner-city, poor populations. The next push by American obstetricians was to move the place of birth from homes to hospitals, where midwives were forbidden to practice." <2> In an effort to entice women into the hospital, ads at the time promised a 'pain-free' childbirth. Unfortunately, what ensued was tantamount to torture. Two drugs were combined to produce Twilight Sleep: morphine and scopolamine. (See more on this practice here.)

The midwives that practiced during this time in American her-story are what I call 'Ghost Midwives', because they entirely disappeared or practiced in secret. The few midwives who did practice in these decades almost never took any students and so it is almost impossible to find a midwife alive today who apprenticed earlier than the mid-1970's. The smear campaign launched by the medical establishment at this time was voracious and effective. Above is an ad from the New England Journal of Medicine at the turn of the last century. Another ad from the same era showed a flattering picture of a clean white male doctor next to a stereotypical image of a dirty female African-American midwife, with a caption describing her as a former slave. Bold text under the photos asked women who they would prefer to deliver their baby, with the obvious right choice being the male doctor. <4> In 1900, over 90 percent of all births occurred in the mother’s home. But by 1940, over half took place in hospitals and by 1950, the figure had reached 90 percent. <5> There were huge areas of the country where midwifery became extinct and 20-70 years passed with no babies delivered by midwives.

Orphan Midwives 1960s - 1970s

In 1960, the world of American women was limited in almost every respect, from family life to the workplace. A woman was expected to follow one path: to marry in her early 20s, start a family quickly, and devote her life to homemaking.

As one woman at the time put it, "The female doesn't really expect a lot from life. She's here as someone's keeper — her husband's or her children's."

As such, wives bore the full load of housekeeping and child care, spending an average of 55 hours a week on domestic chores. They were legally subject to their husbands via "head and master laws," and they had no legal right to any of their husbands' earnings or property, aside from a limited right to "proper support"; husbands, however, would control their wives' property and earnings. If the marriage deteriorated, divorce was difficult to obtain, as "no-fault" divorce was not an option, forcing women to prove wrongdoing on the part of their husbands in order to get divorced.

The 38 percent of American women who worked in 1960 were largely limited to jobs as a teacher, nurse, or secretary. Women were generally unwelcome in professional programs; as one medical school dean declared, "Hell yes, we have a quota... We do keep women out, when we can. We don't want them here — and they don't want them elsewhere, either, whether or not they'll admit it." As a result, in 1960, women accounted for six percent of American doctors, three percent of lawyers, and less than one percent of engineers. Working women were routinely paid lower salaries than men and denied opportunities to advance, as employers assumed they would soon become pregnant and quit their jobs, and that, unlike men, they did not have families to support. <6> Although much of the public debate during the 'Women's Lib" movement about reproductive rights centered on bringing attention to the prevalence of rape and the choice of abortion, a small minority were advocating for birthing rights. In pockets around the country a few women started having homebirths alone or with supportive friends.

The renaissance of non-nurse midwifery became known on a wider scale with the publication of Ina May Gaskin's book, Spiritual Midwifery on January 1st, 1975, chronicling her experience at "The Farm", a hippy commune in Summertown, TN. The Farm community, which originally consisted of a group of over a 100 people who caravanned by bus from California in 1971, chose to have homebirths. Eventually this led to the establishment of the Farm Midwifery Center, and their detailed record-keeping of outcomes appeared in the book.

Other influential books to come out about this time were, The Birth Book by Raven Lang in 1972, Immaculate Deception: A New Look at Women and Childbirth in America, by Suzanne Arms appeared in 1975. It became a best-seller, and was a New York Times Best Book of the Year. Special Delivery by Rahima Baldwin Dancy published in 1979, and then in 1983, Nancy Wainer Cohen published, 'Silent Knife' which the Wall Street Journal called, "The bible of cesarean prevention."

However, at this same point in history, mostly in southern U.S. states, a long and important tradition was being destroyed. Many do not know that the art of midwifery owes much of its influence to black midwives, although there are very few written records of this time (Effland, 2017; Bachlakova, 2016). "Granny midwives" in the south performed all the deliveries for all the black women and for a large amount of the white women too from the slave era all the way until ‘Jim Crow era’ (Lee, 1996). Licensing laws prevented almost all of them from continuing to practice between the 1940s and 1950s (Birthwise, 2016).

Throughout the south prior to the 1940s, there was often not a doctor who was available or would even come to assist a black woman during birth, let alone during her pregnancy (Ehrenreich & English, 2010).

“In that time of segregation, even if black women had money, local hospitals were not interested in having them as patients” (Alabama Women’s Hall of Fame, 2005).

Many of the midwives were referred to as granny midwives; this was because most of the practicing midwives were elder women (Lee, 1996). Midwives were also called doctors and hands-on healers (Ehrenreich & English, 2010). Some even assisted in the death process (Smith, 1951). Sadly, the practice of the southern midwives began to dwindle to non-existence when licensing practices came into the picture (Davis-Floyd, 2006). Black midwives, like Margaret Charles Smith, who is featured in the documentary and the subject of the book, Miss Margaret played an important part in the health of the black family (Alabama Women’s Hall of Fame, 2005). White Eurocentric midwifery and black African American midwifery were on opposite pendulums; the destruction of black community midwifery came to its abrupt conclusion just as white midwifery was beginning its renaissance.

Women who became midwives in this era had no real mentoring in their craft - they were orphans. They had to create, invent, imagine, make-up, and discover ways to attend birth on their own or with the council of medical doctors. Almost every midwife in practice today is a descendant of this renaissance. Naturally the age-old tradition of apprenticeship began again and slowly more and more women began to go to each other's homebirths and learned together how best to attend births. Many decades of medicalized birth, however, influenced even these anti-establishmentarianism pioneers, and at homebirths women would lay down to give birth and depend on their providers to guide the process.

Organized Midwives 1980s - 1990s

Note to reader: During the formation and growth of the various midwifery organizations, mentioned below, the racialized context in the U.S. caused most of the leadership overwhelmingly to come from the dominant white Euro-American culture (Dawley & Walsh, 2016). And in fact today, less than 2% of midwives in the US identify as black.

The students of the 'Orphan Generation' are a very different breed of midwife. In reaction to their laissez faire and largely unorganized learning experience as apprentices, these Midwives became organized. This era could also be called the era of acronyms because the midwifery organizations formed across the country created a kind of alphabet soup. Aside from our nurse-midwifery sister's organization of ACNM, the 'Organized Midwives' created MANA, MEAC, NACPM, CfM and NARM, as well as countless state organizations all including the letter M.

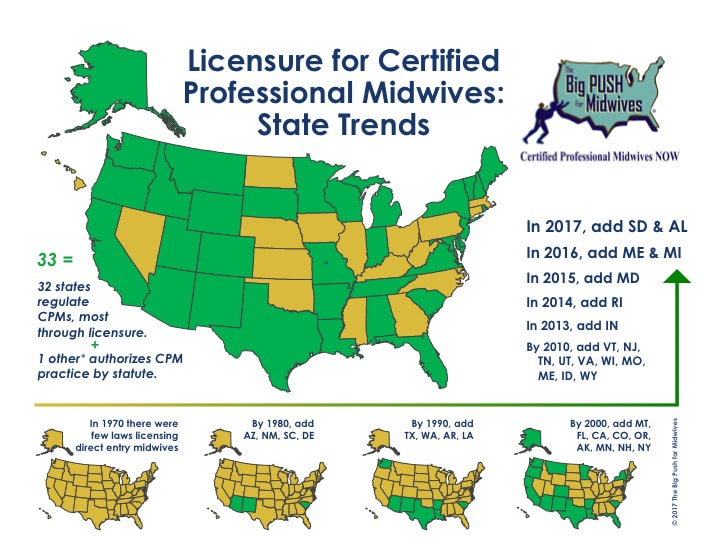

The Midwives Alliance of North America (MANA) was formed in 1982, with the vision and intention to create a national, inclusive, organizing alliance. They created the Certified Professional Midwife (CPM) certification process, and in 1986, launched The North American Registry of Midwives (NARM) to oversee this process. The Midwifery Education Accreditation Council (MEAC) was formed in 1991 by the National Coalition of Midwifery Educators as a not-for-profit organization. Citizens for Midwifery (CfM) is a non-profit, volunteer, grassroots organization. Founded by several mothers in 1996, it is the only national consumer-based group promoting the Midwives Model of Care. And finally, The National Association of Certified Professional Midwives (NACPM) is the membership organization specifically representing Certified Professional Midwives (CPM) in the United States. NACPM, formed in 2000 directs its influence toward promoting, developing and strengthening the profession, improving outcomes for childbearing women and their infants, and informing public policy with the values inherent in CPM care.

This era accomplished a tremendous amount of professionalization, but at a high cost. There was a lot of burn-out, usually an unsustainable level of income and subtle and not-so-subtle territorialism. Because of how hard the organized midwives worked to legitimize their work, they clung very tightly to their ideals of practice, and often had very high expectations for their students.

Simultaneously, many midwives and students alike, frustrated by the lack of organization in the beginning, and then the lack of recognition in the end, chose to hop careers over to nursing or nurse-midwifery. Many an L&D nurse or CNM (especially on the west coast) will admit to being a traditional homebirth midwife in the 70's, or 80's.

These midwives turned away from their grass-roots mentor-midwives, craving structure and systemic steps. They were the originators of the curriculum for all the Direct Entry midwifery training, but found it hard to put all that they learned, often over many, many years into a succinct 3-year process. Consequently, midwives from this generation are aggravated when students anxiously 'count their numbers' like eggs before they hatch.

Ida Darragh, CPM, a midwife in Arkansas and Executive Director of NARM, reiterates, 'A good midwifery education can't just be about the numbers, it's about the development of intuition, and intuition takes time. You can catch 10 babies in a week and that doesn't teach you as much as following 10 women through their whole pregnancy and postpartum experience."

The challenge, of course, is that we lack enough training sites in our nation. As interest in the field of out-of-hospital midwifery grows we have far more students than we have preceptors. Ida agrees: "One-on-one apprenticeship is a very valued way to learn, but its a very slow way to create more midwives. We need more clinical sites in this country." This generation of midwives and the next have had many conversations over the years about the balance between time and numbers in student training, and, as of yet, there doesn't seem to be an answer to the challenge of making more midwives quickly, while maintaining our standards of education. 'Right now, CNM's aren't required to have any out-of-hospital birth experience before graduating, and wouldn't it be great if they did, but there is no where for them to get it, and precious few for CPM's to get", adds Ida.

The major difference between this generation and the next? "The internet," says Ida "Communication can happen so efficiently now. The are no walls, no boundaries, with email we can literally talk with anyone and everyone in the country and the world. Midwives can Google things at birth. This technological change and many others and more still coming out is the biggest difference between midwives who came up in midwifery in my generation compared to the next. I remember when I would send the hand-written notes from my states meeting to the president of the Missouri group and she would send me her's. Indeed, so much is possible now that wasn't possible in this era.

Modern Midwives 2000s - 2010s

The Modern Midwives who managed to make it through their 'sink or swim' apprenticeship, are a dedicated lot. They have rounded many of the sharp edges of midwifery and awakened to their own needs as well of those of mother and babe.

They have embraced formal education and command an impressive knowledge of anatomy and physiology as well as a strong understanding of all manner of policy and procedures of their obstetric counter-parts. This era of midwife places a strong emphasis on balance (although, we may not feel we have achieved the elusive work/life balance in our own lives yet).

When asked to comment, Krista Miracle, DEM, a new midwife serving northern Utah said: "The most challenging piece of midwifery, in my opinion today, is the lack of true leadership and positive role models in midwifery necessary to LEAD women to this profession and mentor them successfully. The midwifery model, one of apprenticeship, has led to abuse of power and lack of accountability. Rather than plant, nurture and grow midwives, we are holding hostage their ability to flourish and in turn decreasing the opportunities for them to serve their communities, and those in need, successfully."

This generation believes in equal access and inclusion, and has been the driving force behind many initiatives to increase access to the under-served and low-income; honor and research multi-cultural traditions and educate the profession on cultural competency; mainstream the profession in all states; legislate mandated Medicaid reimbursement of services; and increase the numbers of midwives who serve people of color. The website, Blackmidwives.org was launched in 2002 from the International Center for Traditional Childbearing (ICTC) and has been instrumental in education and advocacy of this severely under-represented segment of the birthing world.

As much as this generation of midwives wants to grow the profession, they seem to be caught in a vicious cycle.

Experienced midwife, Andi Raine, CPM, LM, IBCLC in NE Wisconsin has this to say about her experience practicing midwifery: "The biggest challenge that I've faced in midwifery is bullying. Midwives of this generation and before so often approach their profession with the energy of scarcity because I think they've had to fight so hard to have it. They've had to fight institutionalized birth, they've had to fight to find an apprenticeship, fight to be legal, fight for a good education, fight for legitimacy, fight for the breath and lives of their clients. And that feeling of lacking abundance, and not having sustainability in this work has caused a wary disposition towards our sisters. Bullying is rampant in midwifery, and it's devastating. There are so few of us that there simply are not alternative peer groups where we can seek support when our local organization is corrupt or disenfranchising. We have been tormented by witch hunts for generations but have also created our own amongst our tribe. Midwifery is a place where you can get shunned just for practicing in someone else's area, or not looking the part. I'm a good midwife and I've had a career attending many hundreds of births over 16 years with excellent outcomes. It's everything I wanted to be when I grew up, and when I'm practicing, I'm fully working within all of my gifts. But I'm leaving midwifery because the hatred shown towards me by other midwives has broken my heart."

Other organizations have also sprung up in support of birthing rights in this era:

The Elephant Circle, founded in 2009, with fiscal sponsorship from the Colorado Organization for Latina Opportunity and Reproductive Rights, brings the strength of advocacy, scientific inquiry, information, and education to issues of birth and reproductive justice, protecting mothers, their children, families, and health providers.

The Foundation for the Advancement of Midwifery (FAM) was founded in 2003. Since its inception, FAM has granted funding to more than 40 organizations representing projects and programs across North America including the United States, Canada, Mexico, Indigenous Nations, and Guatemala. Projects have also been funded that benefit the international community in Haiti and Northern Uganda through MamaBaby Haiti and Mother Health International respectively. Programs and projects funded include critical research on the midwifery model of care, training programs for those serving vulnerable populations of birthing women, public education campaigns targeting consumers, students, and policy makers; and capacity building for midwifery education and licensing organizations.

The Home Birth Summits bring a cross-section of the maternity care system into one room to discuss improved integration of services for all women and families in the United States. In 2011, 2013, and 2014 the Home Birth Summits convened a multidisciplinary group of leaders, representing all stakeholder perspectives, to address their shared responsibility for care of women who plan home births in the United States.

Human Rights in Childbirth believes every woman has the right to be respected as the decision-maker about her own care and her baby’s care. Every healthcare system should be equipped to meet women’s individual needs and personal decisions around childbirth. HRiC is committed to supporting the efforts of individuals and organizations working all over the world to promote the fundamental human rights of pregnant people.

The Asian & Pacific Islander American Health Forum - Asian Americans (AA), Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders (NHPIs) are the fastest growing population in the US. Yet, many AAs and NHPIs still do not have access to high quality services, strong community infrastructure, or a recognized policy voice. The Asian & Pacific Islander American Health Forum (APIAHF) works with communities to mobilize in order to influence policy and to strengthen their community-based organizations to achieve health equity for AAs and NHPIs across the country.

National Latina Institute for Reproductive Health (NLIRH) builds Latina power to guarantee the fundamental human right to reproductive health, dignity and justice. NLIRH elevate Latina leaders, mobilize our families and communities, transform the cultural narrative and catalyze policy change.

Uzazi Village has been established to decrease the maternal and infant health disparities found in the urban core, particularly among African-American women, but also other at-risk populations residing there.

Changing Woman Initiative seeks to draw on cultural strengths to renew indigenous birth knowledge and healing through holistic approaches and community empowerment. It is focused on developing a culturally centered reproductive wellness and birth center.

Commonsense Childbirth's mission is to inspire change in maternal child healthcare systems worldwide. They believe that ALL women deserve a healthy pregnancy, birth and baby!

The Big Push for Midwives provides vital “labor” support to the courageous mothers and midwives nationwide, who sacrifice so much in pushing forward the national movement for out-of-hospital maternity care and birth options, provides public policy and public education experience, highlighting strategies and best practices that have worked, and discusses tactics to avoid that have proven ineffective and empower states to educate more efficiently and effectively for CPM regulation.

Future Midwives 2020s - 2030s

Future midwives are current students. This next generation of midwives express much concern about discrimination and cultural appropriation.

A current National College of Midwifery student, Jessie Rhoads in California, adds: "We're not just accepting the way things were, we're not doing things just because that's the way it's usually done. My generation is asking 'why' a lot and finding that the answers don't always amount to evidence-based practice."

Additionally, many students report significant hardship with apprenticeships citing: lack of access to preceptors of color; restrictive organizational rules that limit and dictate the order and location in which experience must be gained; a culture of abuse with many preceptors, including the hazing by requiring students to do personal errands, childcare, or menial work for their midwives, sometimes for years before being 'allowed' to participate in patient care; and the high cost associated with getting a midwifery education.

Jessie adds: "My generation is a lot less 'woo' than our teachers, we want a more clinically-based education - we want to bridge the gaps between the midwifery and obstetrical models."

It seems like this new generation of midwives is ideally poised to tackle the systemic problems in maternity care and co-create a truly integrated health care system. These students are certainly more visible than any previous generation of students and they are asserting their need for respect. So, too, are they being handed a much clearer picture of their career path with many more resources than previous generations.

They have access to 11 MEAC accredited school in as many states, many offering distance education, US Dept of Education title IV funding, and scholarships. They also have many independent schools that help a student complete the PEP process through NARM.

Additionally, a joint statement among the seven US MERA organizations in 2015 created support for licensure legislation nationally on the condition that it include a requirement for a graduation from a MEAC accredited program or the Midwifery Bridge Certificate. NARM took up the mantel of creating and certifying already credentialed CPM's in the additional required 50 accredited continuing education hours within the five-year period prior to application. The continuing education hours must be in specific subjects. This additional certification may be necessary as some of the last 17 states without a licensure program develop and legislate one and/or in moving us toward state uniformity allowing midwives to transfer licenses easily between states if they move.

Nikki Helms a southern California student at Nizhoni Institute of Midwifery echo's this enthusiasm about becoming a midwife: "I'm excited to become a midwife because it is part of the extensive legacy of African women brought to this country. I am a Midwife of Color, and that, unfortunately, is a rare thing. I am very proud of returning attention to the work of the hands of my foremothers. I, however have a bit of an anxiety disorder, so all this "being on call" business is for the damned birds."

In Conclusion

Lest anyone take offence where it was not meant, let me state that these generational titles were not meant as another way to isolate or separate, but rather as a way to understand the many parts of the whole and give framework to the future generation who enters this profession frequently missing much of the her-story and the nuanced influences in this profession. Additionally, it is my strong belief that, just as in society, each previous generation lives in many of the next generations, I believe this is true of midwifery. We are all in a state of evolution and hopefully all growing toward our best selves in each new era of understanding and professional development.

Midwifery is expanding at an exponential rate. According to the American Association of Birth Centers, a new birth center open in the US almost every month. Homebirth rates have seen as much as a 20% increase in the last decade and for many of the western states the homebirth rate is between 2-6% of the population. But there is so much room for growth as the national homebirth rate sits just at 1.36%. I envision an integrated US maternity system where homebirths are encouraged by all maternity providers for low risk women and a national midwifery usage rate is above 50%. This obviously represents accelerated growth like we've never seen, but luckily we have many successful models of integrated midwifery to learn from in Europe.

In order to meet the consumer demand and offer safe, competent, evidence-based care in every state, we still need to solve many issues as a profession. But I believe it is possible. Please speak up with your solutions and ideas and join me as we live the next era of midwifery!

Comments